Mystic River, March 2025, Somerville, MA

March is a miserable month in New England. It’s not the weather exactly, it’s the unendingness of it—the wind, the cold, the sense of being stuck on the grim paths cleared through the ice and snow that are now just remnants—islands of recalcitrant and filthy ice, accumulated sand, salt, plastic detritus that has emerged from what was once a snowbank to lie useless and exposed along the curb. You can catch sight of crocuses pushing valiantly through the battered earth in places but you have to bend down low with your phone and frame the photo carefully to get all the surrounding misery out of the picture and call it the first sign of spring.

Personally, I get a little Ishmael.

“Whenever I find myself growing grim about the mouth…whenever I find myself involuntarily pausing before coffin warehouses, and bringing up the rear of every funeral I meet; and especially whenever my hypos get such an upper hand of me, that it requires a strong moral principle to prevent me from deliberately stepping into the street, and methodically knocking people's hats off--then, I account it high time to get to sea as soon as I can.”

—Ishmael in Moby-Dick, Herman Melville

In my case, yesterday, this meant going to Assembly Square Mall just off Interstate 93, not to shop, but to park next to the trail that runs along the Mystic River.

I have been thinking a lot about the Mystic River lately—not because of the gritty Sean Penn movie that Clint Eastwood directed by that name, which is probably how most people know of the river today, but because it is at the heart of Medford, the town just outside Boston where I live and because I am writing a book about the history of sugar. Which has led me to Barbados, where the so-called “sugar revolution” occurred at the end of the seventeenth century—a revolution that involved (and this is at the core of the book I’m writing) a world-changing conjunction of large scale agricultural monoculture, the development of the plantation system for ramping up high-intensity extraction from the land and from human labor, and the legal codification of race-based slavery in America. Sugar, slavery, monoculture, capitalism: Barbados.

But also Boston and the Mystic River and Medford, I have learned, where the story is not so much about sugar as its byproduct, molasses.

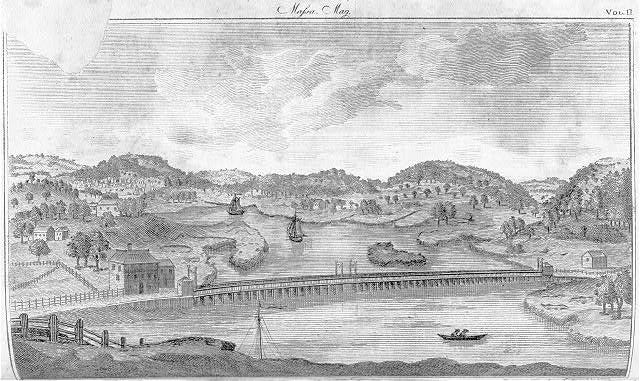

Mystic River, 1790, view from Charlestown. The Massachusetts magazine, or, Monthly museum of knowledge and rational entertainment. (Library of Congress)

I knew about the triangle trade, the alliterative phrase that is lodged in textbooks and our neural pathways but that I have never, as a scholar of the 18th-century Atlantic world, been able to make sense of. Because the “trade” (the euphemism for the unholy market in human beings from Africa to America) was never triangular: the British trade was centered in London, Bristol, the Canary Islands, Africa, the Caribbean, and New England. New England merchants went to the Caribbean with wood and fish and came back with molasses which was made into rum. In Medford. Sometimes they took the rum to Africa, but they also went to England and the Canary Islands, up to Canada and down to Virginia. Triangles were never the dominant geometric design.

Here is the lading bill of a ship, named “John,” that was sent from Boston to Barbados by one Thomas Ruck—a former haberdasher who became a merchant after immigrating to New England in 1638. The ship contained, among other items: four barrels of mackerel, one hogshead of whale oil, six firkins of eels, one hogshead of onions, and“two kentills of refust fish.”

A “kentill” I learn in my research is a “quintal”—a measurement of roughly 100 pounds of fish. “Refust” fish are fish of poor quality or poorly preserved—not good enough for the London market and so diverted to buyers in the West Indies who bought the fish to feed enslaved workers.

A receipt that Ruck later receives shows that he was paid by one James Drax of Barbados, one of the architects of the slave-sugar-capitalism formula who became fabulously wealthy and dined on “Fricases,” “Quelquechoses,” and “Excellent Stews” of beef, pork, and poultry while the enslaved workers on his plantation were on occasion treated to rotten fish.

Sugar Boiling House, Antigua. William Clark, Ten Views In the Island of Antigua (1823)

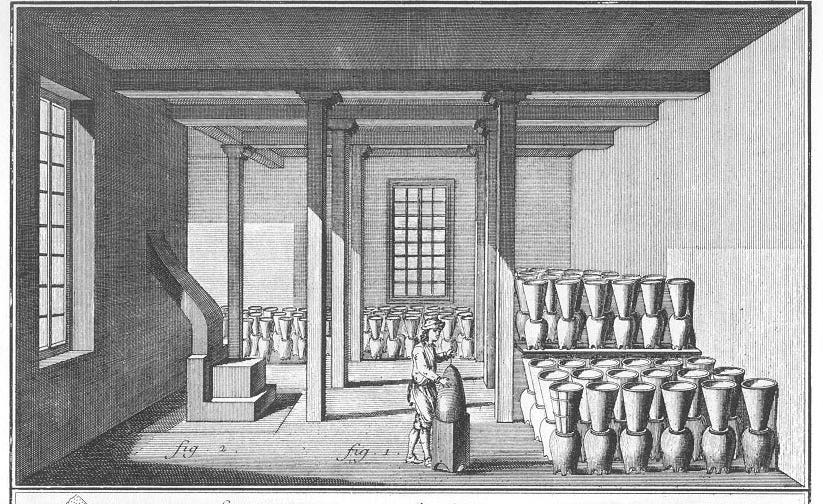

At Drax Hall plantation (which still stands today in Barbados), molasses dripped out of the bottom of upside down ceramic cones into which enslaved workers packed muscovado sugar for drainage after the arduous work of milling the cane and boiling the cane juice in a series of copper cauldrons into a thick, crystallizing syrup. For every four casks of sugar produced, there were three casks of molasses made as well. The British did not like molasses; they liked sugar. So the molasses was sold to the northern colonies where it became gingerbread (like the cookies in Old Hepzibah’s shop in Hawthorne’s House of Seven Gables), Boston baked beans, beer, and especially rum.

Molasses draining from sugar molds. Encyclopédie ou Dictionnaire raisonné des sciences, des arts et des métiers. Paris, 1765.

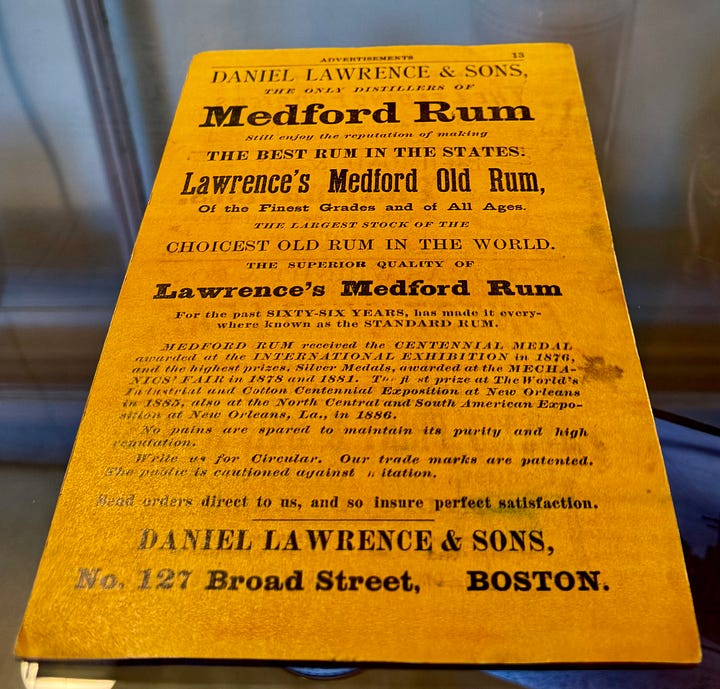

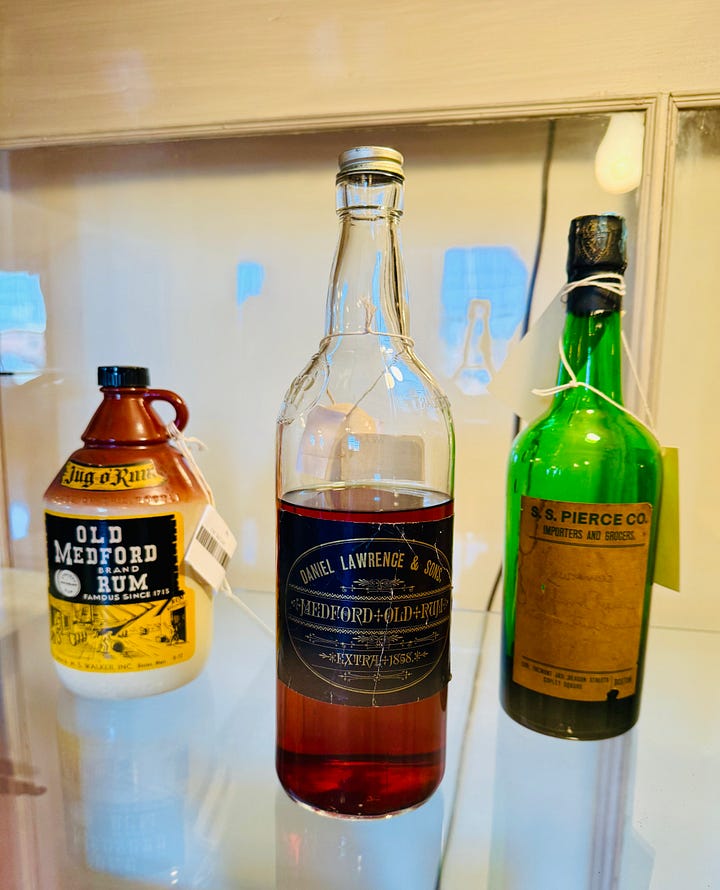

Medford became the center of rum-making, the depot and distillation point of all that molasses. Oak casks of molasses unloaded from the ships in Boston Harbor were transported by water on small boats –“gundelows” and “lighters”—to the docks of Medford. In distilleries owned by the Blanchard, Hall, Tufts, and Lawrence families, the molasses was heated, fermented, condensed, aged, and decanted into bottles of high-proof rum. Some was sold up the coast, some transported inland. The bulk of it did not go to Africa (although plenty did), but rather to British colonizers and to Native Americans against whom rum was weaponized as a tool for taking land. Medford rum was so famous that distillers from other locations passed off their own rum as Medford-made: there was a counterfeit market in Medford rum.

It is strange to be writing a book about sugar and then to find out that the sugar revolution and the origins of chattel slavery and capitalism are linked so directly to the paths I walk every day in the unyielding ice, with my dog Boswell in the streets of Medford.

Usually I walk over the Mystic River, or more often drive over it, without even realizing that there is a river below me because I am travelling on a bed of asphalt or concrete with no sense that there is water nearby. When we first moved to Medford, my husband, John and I went for a run—or tried to—along the river, but the riverbank was inaccessible; brief pathways by the side of the water were interrupted by parking lots, impassable walls, condo buildings. We gave up and sought running routes elsewhere.

But once the opposite was true: rivers were the routes of easy passage at a time when roads were few and often impassable with mud, rocks, erosion, snow, downed trees. Dial back your view two or three hundred years and the river is the center of movement, of possibility, of connection to the world.

Which is why I wanted to walk by the Mystic on a cold Saturday morning in March as if it could somehow take me elsewhere. We parked at the far edge of the lot and crossed two lanes of mall traffic to reach the park—a mile or so of riverbank, an asphalt path for joggers, of which were few, a thawing strip of beaten grass and a thin line of bare trees next to the water. As we walked, the wind whipped at us and raised whitecaps on the brown water of the river. I passed the dog’s leash to John to hold as I stopped to take photos of the cautionary sign about sewage outflow in the river.

I know that the Mystic River was once flush with small herring—alewife fish. The alewife has a protruding belly that may be the source of its name—like the rounded bellies of the wives of tavern owners. Or possibly the name has Native American roots—also a plausible etymology because the Mystic teemed with alewives that were harvested by the Massachusetts people who plied the river in canoes.

The alewife species is one of a very few that are anadromous—able to live both in salt and fresh water. That’s what the Mystic itself does—it connects the freshwater from land to the saltwater of the sea, and so it became a central spot for rum, which came from molasses, which came from Barbados, and once distilled, went by land and sea to soldiers, to sailors, and to traders who used it to kill pain, to buy beaver pelts, to sleep, to sing, to extort Indigenous land. From sea to land, from land to sea. The alewives still swim in the river today, but in far reduced numbers; sewage released into the river chokes off the oxygen and they can’t breathe and dams keep them from returning to their spawning grounds, although the Mystic River Watershed Association has had success in installing fish ladders that are helping to bring them back.

Alewife: Alosa pseudoharengus. Painting by Ellen Edmonson

Before the Mystic was straitened by dams, locks, and retaining walls, it was a tidal river surrounded by salt marshes. In the seventeenth century, the Massachusetts leader Saunkskwa of Missitekw lived upriver on the west side of Mystic Lake after colonists including John Winthrop claimed large swaths of land along the banks closer to the bay. In the nineteenth century, when the tide came up through the marshes, boys jumped from the docks in Medford to swim, or “bathe” as the language had it then.

“Twice a day the salt sea water came sweeping by, bringing the real sea air into the town, and in springtides covering the wide marshes,” writes one Thomas Stetson of his Medford boyhood. “Crowds of boys came here to bathe at high water, for no well conditioned Medford boy would ever bathe except at the top of the flood.” The dock the boys jumped from was crowded with casks of rum and molasses “hissing in the sun” and the air smelled of salt and molasses and rum. “The molasses casks came without any bungs, its odor went to the skies almost as rummy as the rum itself.”

John and I headed west, up the river on land which was once part of John Winthrop’s 200 acre plantation, Ten Hills Farm, which stretched from Assembly Square to downtown Medford. We passed on a boardwalk under the geometric arch of the Wellington Bridge which carries four lanes of traffic across the river on Rte. 28. There’s a plan for a pedestrian bridge in the works, but construction is stalled. John told me he once saw a photo of his father as a young man, swan diving off the Wellington Bridge into the Mystic. It’s an image that has haunted him because his father looked so free; he had a medal on a chain around his neck that was flying backward over his shoulder in the photo. It haunted him because he did not know his father could dive like that and because his father never taught John to swim.

Sometime after that photo was taken, his father got married, gave up ideas of a college education, took a job with the Cambridge Gas Company reading gas meters, fixing furnaces, and fathered six children. Growing up in Somerville when it was a dense maze of triple-deckers full of Irish and Italian first- and second-generation immigrants, John did not swim in the Mystic: he crowded with his many siblings into the Dilboy public pool and stayed in the shallow end for years because no one had the time or resources to teach him to swim. For John, the memory of the photo is unmooring, a morass of old feelings of longing, anger, shame, and love. He hasn’t seen the photo in years, and none of his siblings recall seeing it; it’s now gone under, submerged into the past.

We walked along the scrim of land and trees between the river and the Ten Hills neighborhood. I told John about Winthrop’s 200-acre farm and the molasses; he told me about his father and the lost photo. I took pictures with my phone of the street signs: Governor Winthrop Road, Puritan Road, Putnam Road. On Bailey Road we turn left away from the river because Bailey Road is where John’s father grew up and he wants to see the ancestral home that, like Winthrop’s stone house, is no longer there. His father’s home was destroyed by the state, taken by eminent domain in order to build I-93 in the mid-60s. On one side of Bailey Road are vinyl-clad double deckers; on the other a retaining wall on the far side of which two hundred thousand cars pass daily.

The Ten Hills neighborhood is cut off in every direction now, a pie-shaped slice of neighborly streets, bordered by the unswimmable river, the uncrossable interstate and the high-traffic Rte. 28 which crosses the Wellington Bridge. It’s the world of the Penn-Eastwood “Mystic River”—a movie that John could not watch for more than a year after it came out because it was a little too close to the world he grew up in. A world in which the exits were blocked and some of the escapes were worse than staying put. In the neighborhood where he grew up, John told me, every kid knew that you never got in a car with a priest. It was just a thing you knew. Clint Eastwood’s camera in “Mystic River” turns the river and the Tobin Bridge, downstream from the Wellington Bridge, into the walls of a prison, inside of which lies repeating violence.

John Dillon, 82 Bailey Road, Somerville, MA.

I take a photo of John in front of what was once 82 Bailey Road. We walk to the end of the road where our path is blocked by Rte. 28 and we turn around, back to the river path.

I think about the paths we take and how they pave over other histories, other possibilities, just when in March, I can no longer bear the paths I repeatedly tread, that constrain me to repetition, to the tired patterns of my own mind, the narrow rounds of life.

Thinking about the gundelows, the canoes, the lighters, the molasses casks, the refused fish, the ways that Boston built itself on the land of the Massachusetts people and the labor of enslaved Africans and then erased the story and produced famous Medford rum. Claimed a gorgeous river and then erased it too, with interstates and sewage. But still, in the wind and the sun walking along the shore of the river, thinking about these histories opens something for me. Turns the internal impasse into shifting terrain, palimpsestic stories of choices made in the past, choices that might have been different, choices that could still be made today to change the course of roads and rivers, to break barriers of loss and violence and dispossession. Gazing out at the river and its history as I walk on the thawing earth of the river’s verge, I conjugate verbs beneath my feet: was, is, will be, could be, could have been, could be to come. That and the sun on my face feel good, even in the strong wind that grabs the car door out of my hand when we return to the car in the parking lot next to Burlington Coat Factory, Trader Joe’s, Staples, and Starbucks.

Just wow. Just went in March, I can no longer bear the paths I repeatedly tread. I conjugate verbs beneath my feet. Elizabeth, your writing is beautiful. Layered, like our history.

Elizabeth, In addition to being beautifully written, this is so interesting! My family is in Salem and Marblehead so I'm familiar with the important role Salem played on the trade routes, including exchanging for molasses. Have you explored what the Peabody Essex Museum might offer in the way of research resources? This exhibit speaks to molasses and rum:

http://alchemy.pem.org/in_pem_collection/